Evergreen

Valley

Stoneham,

Maine

1972-1975,

1976-1982

Introduction ~ Scott Andrews Article ~

Additional Notes and Photos ~ Readers Memories

Please note the Evergreen Valley Inn is in operation and is a great place to

stay - check it out at Evergreen Valley

Inn.

Introduction

Evergreen Valley was a medium

sized ski area with a troubled history, bankruptcies, and a relatively short

existence. It was one of the last major ski areas to be developed in New

England, finally opening in 1972, and only lasted for ten years (including a

closure form 1975-1976). It had a 1050' vertical drop and three Mueller lattice

tower chairlifts. The area closed in 1982, lifts were removed in the early

1990's, and today, the trails are very much grown in. However, the huge base

lodge still stands and apparently is still rarely used.

Scott Andrews Article

Scott Andrews wrote a

terrific article summarizing Evergreen Valley's development, and best

illustrates the history of the mountain. Many thanks to Scott for allowing us to

use the article below! I have added additional photos into the article to help

illustrate its history.

For even more information,

please visit the

Lovell

Historical Society's newsletter on Evergreen Valley.

SHOOTING FOR THE MOON

In the boom-bust years of

the Maine ski industry, Evergreen Valley stands out as the most egregious

failure

By

Scott Andrews

Copyright 2008

Among the dozens of ski areas

that were constructed in Maine and New England during the boom-and-bust era of

the 1960s through 1980s, Evergreen Valley was the biggest and most infamous

failure by several key yardsticks.

Measured by its three

chairlifts ─ a widely used indicator of a resort’s size and stature ─ Evergreen

Valley was the region’s biggest failure. Figured by its $7 million investment,

it was the costliest failure. In terms of its multi-year bankruptcy proceedings

and multiple lawsuits, Evergreen Valley was the longest-running failure. And

measured by the hundreds of column inches of news coverage, it ranks as the most

notorious failure.

Indeed, a perusal of the

dozens of newspaper stories that chronicled the vision, struggles and ultimate

demise of Evergreen Valley suggests a melodrama with a rather theatrical cast:

honest but unsophisticated small-town businessmen, cunning consultants,

audacious architects, greedy financiers, bumbling bureaucrats and politicians ─

plus a few outright charlatans, con men and crooks.

Interest in Evergreen Valley

has been increasing recently. The long-defunct resort is currently featured in

an exhibit at the New England Ski Museum in Franconia, New Hampshire. The theme

is “Lost Ski Areas of New England” and the exhibit runs through this coming

spring. It was inspired by a recently published book, “Lost Ski Areas of the

White Mountains.” The book was written by Jeremy Davis, the founder of the New

England Lost Ski Areas Project and the webmaster of its well-visited Internet

site ─ www.nelsap.org. (In Davis’ parlance, “lost” means “defunct and

disappeared.”)

On behalf of Ski Museum of

Maine, the present author is currently researching aspects of the Evergreen

Valley story as part of a series of “Fireside Chats” to be presented around the

state over the next few winter seasons. The overall project is titled

“Down-Mountain and Cross-Country: 140 Years of Skiing in Maine.” The first

“chat” of that series ─ an overview of the entire historical span with digital

slideshow ─ will be presented November 23 the Lovell Historical Society.

At the request of Cathy

Stone, executive director of the Lovell Historical Society, the present author

is sharing some thoughts and observations on Evergreen Valley’s sad saga.

A TRAGEDY IN THREE ACTS

Even when stripped of its

most theatrical details, the story of Evergreen Valley still resembles a modern

variation on a theme from ancient Greek tragedy ─ a classic case of hubris

leading to struggle and finally to a fall.

Within the ski industry,

Evergreen Valley is mostly remembered in more pedestrian language ─ as an

egregious example of overreaching vision followed by underachieving results.

But Evergreen Valley didn’t

start as a big project. In fact, its beginnings as Adams Mountain Ski-Way were

quite unpretentious, even by the very modest standards of its times. But its

basic business model was flawed, and a succession of setbacks and obstructions

were swept aside with an obstinate, bull-headed determination that continually

up-sized the scope of the enterprise and upped its financial stakes.

The inherent problems of the

undertaking ─ coupled with an overextended management team, an ill-starred

building process, a changing economic and regulatory environment and a number of

questionable business decisions ─ led to an economic tragedy that began in 1961

and was largely played out by 1991.

Most of the key events took

place during that 30-year time span; by chance, the story conveniently divides

into three periods of roughly equal length.

The first phase traces the

Evergreen Valley story from its initial concept in 1961 to the first of its many

business calamities ─ about a year before the resort opened for skiing in 1972.

The second spans a decade of

operation. Evergreen Valley opened for three seasons of skiing before shutting

down for a one-year hiatus due to bankruptcy. Then six seasons of renewed

operation were followed by a year of tumultuous death throes.

The last period recounts

Evergreen Valley’s final struggles and denouement ─ ending when the three

chairlifts were dismantled in 1991 and skiers abandoned hope that they would

ever again schuss down the slopes.

CAN-DO ATTITUDE

Skiing was a booming business

in the late 1950s and early 1960s, both in Maine and the U.S. as a whole. The

shining example was California’s Squaw Valley Resort. In 1955, Squaw Valley

boasted only one chairlift plus the stunning vision of one man, owner Alex

Cushing, who successfully lobbied the International Olympic Committee to award

him the 1960 Winter Games. Some observers regarded Cushing’s proposal as

impossibly bold, but his huge ski resort was built almost overnight and Squaw

Valley hosted a very successful and enormously visible Olympiad.

Squaw Valley epitomized

America’s can-do attitude as well as its engineering and economic might. Many

New England skiers were involved in Squaw Valley’s construction and the conduct

of the 1960 Winter Games. For the first time, Olympic competition was televised

live. Squaw Valley made a powerful statement for all the world to see: America

was a major skiing nation. Nearly half a century later, the resort itself

remains one of the world’s largest and most popular places to ski.

In the East, Wildcat Mountain

in New Hampshire and Whiteface in New York were the most ambitious and exciting

new ski areas developed in the late 1950s. Both boasted more than 2,000 vertical

feet and both opened in January, 1958. Several large resorts also opened in

Vermont during the 1950s.

Locally, Pleasant Mountain

and Sugarloaf were expanding rapidly throughout the 1950s, while Sunday River ─

hailed by the Portland Press Herald as Maine’s third major ski area ─

opened late in 1959 with a rope tow and a single T-bar. Mount Abram debuted the

following year. In 1960, two ski developments were being built simultaneous in

Rangeley, while at least a dozen others were planned or under construction all

the way from the southwest coast to Aroostook County.

In virtually all cases in

Maine, the developers and visionaries were local businessmen who attracted

community support by promising a (partial) solution to a painfully self-evident

problem that any rural resident could fathom: the long-term decline of farming,

logging and traditional forest products industries.

In Brownfield, the proposed

Burnt Meadow Mountain ski area was also billed as helping the town recover from

the devastating forest fires of 1947. In several of these enterprises,

government assistance was sought ─ and often granted ─ via a number of state and

federal economic development programs.

Why shouldn’t residents of

Lovell and Stoneham join the throng and create a ski area of their own to boost

their own local economies? A plan was adumbrated at the 1961 town meetings, and

a three-member joint follow-up committee was appointed. The first concrete

proposal was called Adams Mountain Ski-Way, a moniker that mirrored Sunday

River’s original name.

None of the original trio had

experience in the ski business, but they sought help from a well-established

leader in the field. A study was commissioned from Sno-Engineering, a New

Hampshire consulting firm that had previously worked on Sugarloaf and Sunday

River. Sno-Engineering was headed by Sel Hannah, who was involved in many

successful ski area developments. The company’s plan included one T-bar, a

handful of trails and a small lodge. Most of the skiing acreage would be leased

from the White Mountain National Forest, a common arrangement. Hannah estimated

a cost of $299,000 in 1962.

OVERREACHING VISION

Two years passed and little

had been accomplished except that the first plan had morphed into a simple

four-season resort by adding a nine-hole golf course. And the price tag was

lifted to $550,000. The original idea of 100 percent private financing was soon

dropped ─ lack of local money to invest in shares ─ in favor of funding via a

small stock sale to supplement a proposed $500,000 federal loan.

After the loan request was

denied, most entrepreneurs would have either given up or gone back to the

drawing boards to scale down their plans.

But not Evergreen Valley, as

the enlarged concept was now known. Instead, out-of-state promoters, investors

and bankers and brokerage firms were invited into the enterprise, and their

visions grew exponentially in expanse and expense. Within a few years, the

up-scaled scheme called for a full-blown $5-million four-season resort, complete

with 18-hole golf course, indoor tennis courts, marina on Kezar Lake, riding

stables, hotel, retail stores and second home development as far as the eye

could see. The centerpiece of the 2,000-acre expanse was a vastly enlarged ski

area ─ complete with dozen-plus trails, three chairlifts and Maine’s biggest and

grandest base lodge.

At full build-out, Evergreen

Valley’s cost was figured around $40 million. Maine had never seen a ski resort

on this scale. It was certainly grossly out of proportion to Adams Mountain’s

very modest 1,050 vertical feet. But by that point, Mainers were no longer the

driving force.

“Evergreen Valley became a

hugely ambitious project, probably because the locals started using outside

consultants who saw big opportunities,” explained Jeff Leich, executive director

of the New England Ski Museum.

|

Successive iterations of

revised plans and construction change-orders were inextricably coupled with

ongoing financial turmoil, with many personalities and companies entering and

exiting. Years passed as millions of dollars were spent. In one 1971 tally, the

total money spent was figured at $4.6 million, with an astounding 35 percent

going to various professional fees. Legal bills alone consumed $300,000 ─ more

than Hannah’s estimate for the entire original plan.

But at least $2.9 million was

poured into construction. The growl of bulldozers, the whine of power saws and

the thuds of hammers echoed off Adams Mountain. And the wop-wop-wop of

helicopters was heard for miles around as the three chairlifts were transported

up the hill and assembled.

But Evergreen Valley, by now

the largest ski resort ever constructed in Maine, had yet to open.

Recurring financial crises,

regulatory hurdles, management stumbles and cost overruns were fodder for the

press. In March, 1971, in the midst of the tumult, one of Evergreen Valley’s

original visionaries was interviewed for the Maine Sunday Telegram, and

he continued to express optimism.

“This country made it to the

moon and back,” said Ervin Lord, a retired game warden who was officially in

charge. “We were shooting for the moon too when we started this thing. I think

we’re going to make it.”

But not in 1971. The

announced December opening date was put off again while Evergreen Valley

wrestled with financial crises and regulatory matters for another year, emerging

with a new owner.

|

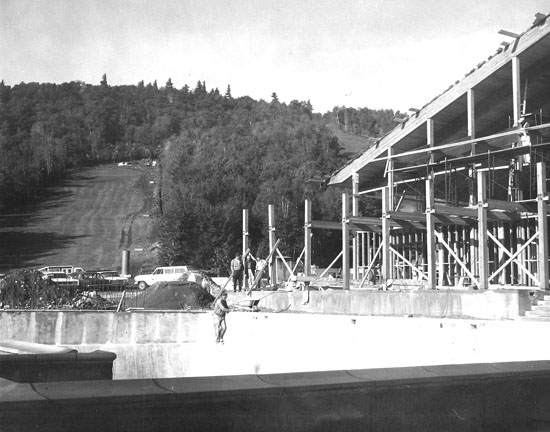

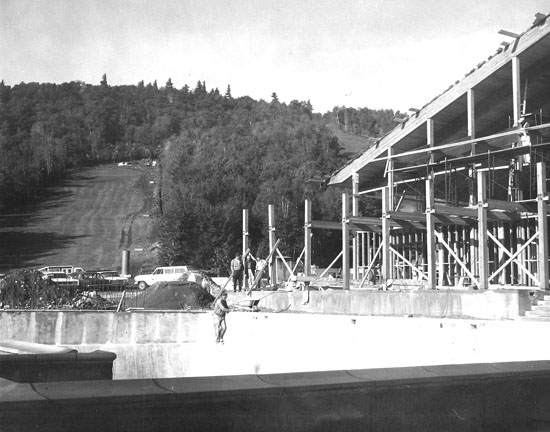

Construction of the base lodge, likely

~1970, from Jon Regan. You can see the

beginner slope in the background without its chair installed. This was

the Spruce Up slope. Click on the image for the larger version. |

SECOND LAKE PLACID?

Despite a decade of failure

and frustration, when Evergreen Valley finally opened to skiers on December 16,

1972, it boasted Maine’s biggest and most elaborate base lodge, an

architecturally imposing edifice that included a heated outdoor Olympic-size

swimming pool. Many New Englanders chuckled at the of the 28,000-square-foot

building’s distinctively Western look. But that wasn’t really too surprising: A

consultant based in Seattle, Washington, was in charge of the project when it

was designed and constructed. The massive timbers had been shipped all the way

from Oregon.

Three Swiss-built double

chairlifts were turning ─ the longest ran 4,544 feet to the summit of Adams

Mountain ─ and the nine ski runs were groomed by state-of-the-art Pisten Bully

snowcats. About half of the terrain was lighted for night skiing. Ten miles of

cross-country trails radiated into the surrounding forests and offered miles of

pleasant ski touring. No ski resort in the state ever offered so much on its

opening day.

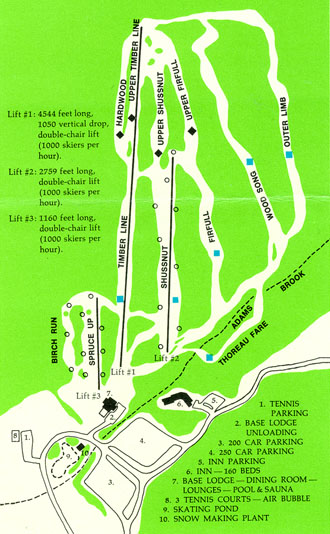

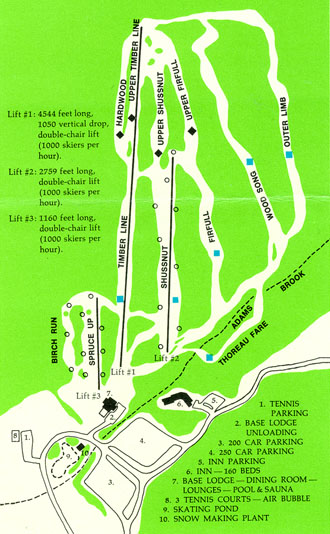

|

An undated trail map shows the completed

ski area. Click on it to view the larger version. Note that night skiing

was also available, and that the air bubble tennis courts are mentioned.

(Jeremy Davis) |

At a cost of $7 million

(estimates of the exact amount vary) it was also the most expensive. Most of the

investment was guaranteed by the state of Maine. A special act of the

legislature had been required to authorize an amount that large. That

legislation, in turn, was the result of a lawsuit filed by Evergreen Valley.

Leich summarized the dilemma:

“It took more than 10 years for Evergreen Valley to open, and by the time they

did, they’d gone from the era of the early ‘60s, when it was easy to open a ski

area by putting up a T-bar on a mountain and cutting a few trails, to the era of

the early ‘70s, when skier growth had stopped and environmental regulations were

making it much more difficult to develop an area.”

But those problems were

temporarily set aside when Evergreen Valley welcomed its first schussers.

Optimism prevailed, at least for a season or two. Ralph “Woody” Woodward, one of

New England’s most respected ski school directors, was hired to oversee all

facets of outdoor recreation. In addition to 15 ski instructors, Woodward also

supervised a variety of summer operations at Evergreen Valley such as a

conservation camp.

“I always thought that it

could be the second Lake Placid Club, on a smaller scale,” recalled Woodward,

drawing a comparison to the world-famous resort in New York’s Adirondack

Mountains.

“The ski area was small but

adequate,” he added. “It was mostly intermediate terrain; we didn’t have

anything for the experts. Snowmaking was limited, but grooming was excellent.”

Peter Cox, writing for the

Maine Times in 1973, largely concurred with Woodward’s assessment: “My guess

is that this will become a very popular family resort for those who are more

interested in a nice vacation than bouncing off moguls.”

But Woodward also noted

problems of proximity and access; the resort was distant from major highways and

good roads. “That far back in the woods, people don’t find you,” he opined.

Aggressive marketing was needed, but Woodward thought that Evergreen Valley

management did little.

“They didn’t put any money

into advertising,” he said. “They didn’t go out and get the people.”

|

|

OPEN-AND-SHUT CASE

And why should skiers make

the extra effort to drive to Evergreen Valley? Or why should they invest in a

topnotch vacation home? With only 1,050 vertical feet, the exceptionally

expensive resort was exceptionally ordinary by ski industry standards.

Among Maine ski areas,

Evergreen Valley ranked smack in the middle of the competitive pack, equal to

Mount Abram and substantially less than either Pleasant Mountain or Sunday

River. And the oft-noted lack of expert terrain hurt its reputation among the

serious skiers who constituted the core of the market then and now.

The ski area ─ the only part

of Evergreen Valley to become fully operational ─ sputtered for a decade before

the lifts last turned in spring, 1982. It operated a total of nine seasons ─

being closed for the winter of 1975-1976 due to a bankruptcy.

It wasn’t the only ski area

to struggle. During the 10-year period when Evergreen Valley was open, more than

a score of other Maine ski areas went out of business. A succession of low-snow

winters plus the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973-1974 were important contributing

factors. Three of the failures were “major areas” ─ defined as having at least

one chairlift. These were Bald Mountain (near Bangor),

Big A (in York) and

Enchanted Mountain (near Jackman). The other dropouts were much smaller; they

included Burnt Meadow Mountain and

Ski-W.

|

Skiers near the summit of Evergreen

Valley. Date unknown. Courtesy Laurie P. |

|

Although it did open for

skiing, Evergreen Valley’s far grander vision of a vast four-season resort never

really flew. The marina had a few boats at a couple of docks, served by a small

building. Half of the golf course was finished. A portion of the inn was built,

plus a few condominiums and a 30-stall riding stable. The covered tennis courts

were completed, but the pressurized inflatable bubble unfortunately proved to be

a frequent target for hunters. The retail complex was never started.

Some might argue that

Evergreen Valley was ahead of its time by pointing out that Sunday River and

Sugarloaf successfully morphed into somewhat similar multi-season business

models. But the process took 20 years and those resorts are anchored by much,

much larger ski areas and supported by national and international marketing

campaigns. And they struggled mightily, with Sugarloaf actually going through

bankruptcy in the mid-1980s.

What’s the legacy? Evergreen

Valley’s inn and a few condos remain today. The imposing million-dollar base

lodge remains standing but seldom used ─ mute testimony to the scope of the

failure.

The ski area’s death throes

lasted from 1982 through 1991. The unhappy decade that followed the 1981-1982

ski season is punctuated by a variety of proposals to re-start the resort,

punctuated by a few moments of black-comic relief.

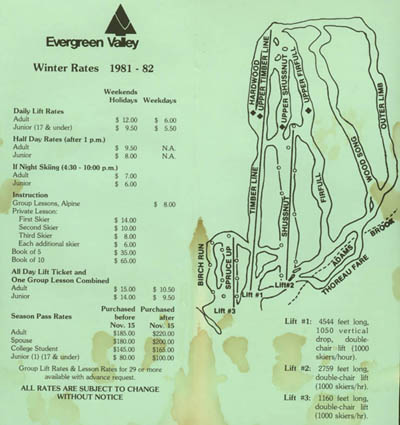

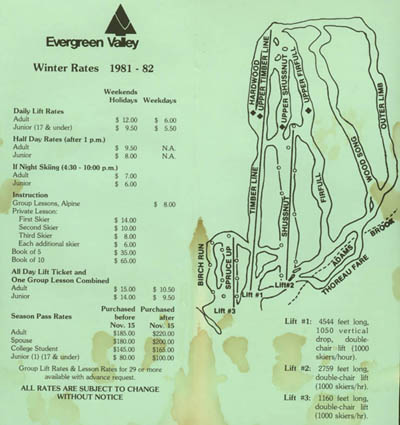

(Right - the trail

map and brochure from Evergreen's final year of operation, 1981-1982.

Click on it to view the larger version.)

|

|

|

|

The Finance Authority of

Maine was the owner for much of that period, and repeatedly tried to unload its

economic white elephant on a variety of operators. One of these was Evergreen

Recreation Corporation, which announced in October, 1984, that skiing would

return that coming season. But details of the proposed accord couldn’t be

resolved and the company walked away from the deal in November. The lifts never

turned.

After this proposal soured,

another rescue was attempted in 1986 when a local businessman agreed to purchase

Evergreen Valley, announcing that he would shortly re-open for skiing and other

business. But shortly after closing on the real estate, he tried

(unsuccessfully) to unload his newly acquired problem.

Left - the aerial

view from 1997 shows that the trails were still visible but growing in

fast!

|

|

The entire saga of Evergreen

Valley from start to finish is documented in excruciating detail in a

nine-volume set of papers owned by the Lovell Historical Society.

For skiers at least, one of

these documents closes the torturous case. The prolonged shuttering of the ski

area violated the terms of the federal land lease, and National Forest Service

ordered Evergreen Valley to remove the lifts in 1991.

Of the three double

chairlifts, the concrete platforms of the lower terminals are the only remains

that are visible to the occasional curious visitors who stop by to gaze and

wonder.

|

The trail map for Evergreen Valley still

hung outside the base lodge, 1999 (Jeremy Davis).

|

(End of Scott

Andrews' Article)

Additional Notes and Photos

In the mid 1990's,

Mars Hill Ski Area, now known as Big Rock,

purchased the summit chairlift, where it now operates as their summit lift. They

also purchased their snowmaking equipment.

Another chair apparently was

purchased by Black Mountain of Maine, according to John Snowe, but was never

installed.

The following stats regarding

the three chairlifts are courtesy of

Skilifts.org:

Chair #1 (Summit Chair):

4616' long, 1037' vertical, 1000 skiers per hour, 500' per minute.

Chair #2 (Mid Mountain): 2828' long, 603' vertical, 1000 skiers per hour, 450'

per minute

Chair #3 (Beginner Chair): 1200' long, 248' vertical, 1000 skiers per hour, 350'

per minute

More photos of the Evergreen

Valley pool can be found

here.

Evergreen Valley was quite unique in that it

never had a surface lift! There are very few cases of this in New England where

a resort operated with just chairlifts and nothing else.

| I (Jeremy) visited this

area in 1999, after visiting Norma King and her husband Dick in Lovell.

Norma (aka "Sunshine") was my museum manager at the Mt. Washington

Observatory that summer, and one of the nicest people you'd ever meet.

They lived a couple of miles away and took me to the ski area in their

jeep. We walked around the base area and took the following photos.

The inside of the base lodge (taken from

the window) in late August, 1999. While it looked very clean and

organized in there, you can tell the decor is straight from the 1970's.

The price board in the kitchen showed prices from the early 1980's.

Downstairs, through a window, we saw a calendar from 1984. |

|

|

|

More of the lodge, August, 1999. |

| Looking up the summit liftline, nearly

grown in as of 1999. |

|

|

|

Here's a view of the lodge

taken sometime in the early 2000's, thanks to Will Wilcoxson.

|

Jeremy Clark's Photos:

| Jeremy Clark visited this

ski area in March of 2009, and took the following winter shots. Here's

the base lodge. |

|

|

|

Looking at the base lodge from the

base of where the summit chair used to run. |

| The sun sets over the summit liftline. |

|

|

|

The summit has a great

view, and some of the trails here are clearer than the bottom slopes. |

| The concrete foundation for the summit

double chairlift remains. |

|

Readers Memories:

Outin21: As a

teenager in Maine in the 70's I did ski Evergreen Valley a number of

times. Two small notes. They did try to promote a big "Rock" Concert there in

the mid 70's. It was supposed to be a huge event. I don't think it went too

far. Secondly, we were all just a bunch of

ski bums in So. Maine and we would ski anywhere. The big "knock" on

Evergreen was that it was "TOO" groomed. It never had a mogul or bump on it.

We thought it was boring.

Stephen Provost: Evergreen was

reopened once or twice during the late 1970's. I distinctly remember skiing

there on a beautiful December day in 1978. Maine received an early snowfall that

year and Evergreen was open for business. It was a great mountain with a lot of

potential. It was too bad to lose that one.

Paul Reuben: I

skied Evergreen Valley many times in

the early 70's and as a kid it seemed to have a much larger vertical than 1050

ft. I really wanted it to make it. People always preferred Pleasant Mountain

though, it never really drew the crowds, even though it was a great resort, with

a really cool outdoor heated pool. You could see Pleasant Mt. From the summit.

John Snowe: I

skied at Evergreen Valley with the Walton School Ski Club in 1973 and again with

my family the same year. I remember the skiing as being good, but there was

nothing for the expert. The place had a beautiful lodge with a wonderful

fireplace and the heated outdoor pool. The heated outdoor pool was quite the

extravagance in 1973 during the first oil crisis. I cannot remember seeing

anybody actually in the pool. In the past few years, I have been to the

Evergreen Valley site where there are still some active condominiums. I helped

people at the site replace some hardware on some

water storage tanks. Being

a golfer, I was sorry to see that the golf course at Evergreen Valley is all

grown over.

A chairlift from Evergreen Valley is now owned by Black Mountain in Rumford, but

it has never been installed.

Hannah Warren: I remember when the built Evergreen

Valley. My brother was an engineer who helped on the plans for the septic

system. They put in a 3rd stage septic system. Quite advanced for the era.

Fryeburg's ski team used to do land training on the slopes in the fall before

snow. It was a great place to ski, but even coming from Fryeburg it always

seemed like it was in the middle of nowhere. Skied there a couple of times when

I was in college. Even ran into old friends from Pleasant, that recognized me

from my orange jacket.

Brian Fox: I grew up skiing at Evergreen Valley in

Stoneham, Maine as a kid. My grandfather actually helped build the slopes, and

my father's office building was once used as a

state police staging point for a huge

summer rock concert that

was held at the mountain, just before it's downfall.

If you remember Evergreen Valley and have

more photos, please let us know.

Last updated November 25,

2009

Head

back to Lost Maine Ski Areas

Head

back to the main page